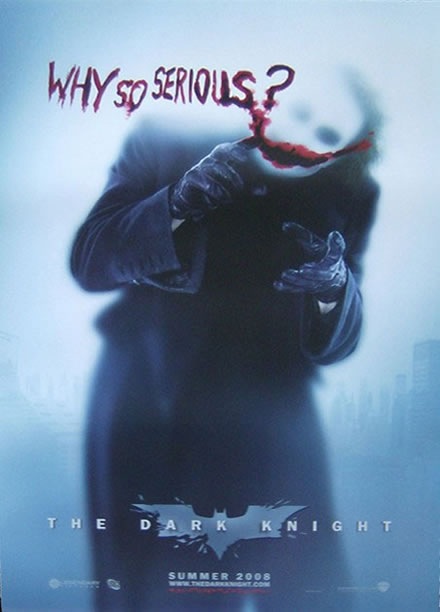

I have no idea what I can say about this movie that hasn't been said somewhere, even though it's only been out three weeks. For posterity, though, here are a few of the many things I liked:

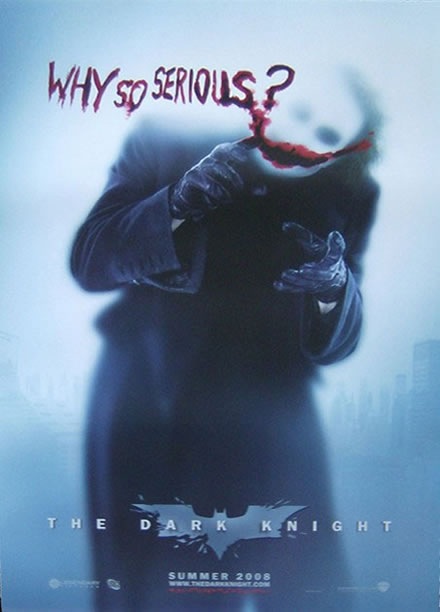

1) I'm no judge of acting, but I was on edge whenever Heath Ledger's Joker was onscreen.

2) The opening heist scene was both tense and a perfect intro to the Joker's methods and morality.

3) The shot of the Joker hanging his head out the window of (I forget) either a cop car or the semi-truck. Some people have suggested the movie should've ended there, and I can see their point.

And a few of the things I didn't:

1) Two-Face's transformation felt rushed, and added another prong to the story that I didn't think needed to be there -- save him for the third film.

2) I had no idea what the hell was going on in the waterfront scene before Batman's final showdown with the Joker.

3) Some of the obvious tie-ins to today's political situation took me out of the movie. For example, Batman's wiretapping policy -- when Morgan Freeman says, "This is wrong," I almost groaned. Now of course, spying on an entire city during a normal day is wrong, but this is the ticking time-bomb scenario that never actually happens in real life but happens all the time in the movies. All Batman wants to use this for is to find the location of the Joker, who he knows is going to kill a lot of people that day. The whole situation is an obvious Patriot Act reference, but if we're really supposed to contemplate the ethics of our real world government, we can't really do it in such a fantastic scenario (one that pro-domestic spying and pro-torture folks will invariably bring up to try to justify these kinds of tactics). Freeman's line comes off as a half-hearted sop to the left so the movie can at least give the appearance of exploring both sides of the issue when really, there's only path for Batman to take to save Gotham. The executive producer of 24, a registered Democrat, said something interesting about that show's tendency to justify torture: "The politics of the show are narrative politics." Batman was just following narrative politics.

That gripe aside, I liked a lot of the other inquisitions into whether Batman's presence and actions helped or hurt Gotham -- it's suggested that Batman helped inspire villains like the Joker ("You complete me"). In that respect, it's like several other Nolan films since Memento. As an auteurist whore, I'm happy to find thematic connections between his "artier" films like Memento and The Prestige and blockbusters like the Batman franchise. He seems to be interested in issues like the psychic toll of fighting injustice, the thin line between justice and revenge, guilt, the power of memory, etc.