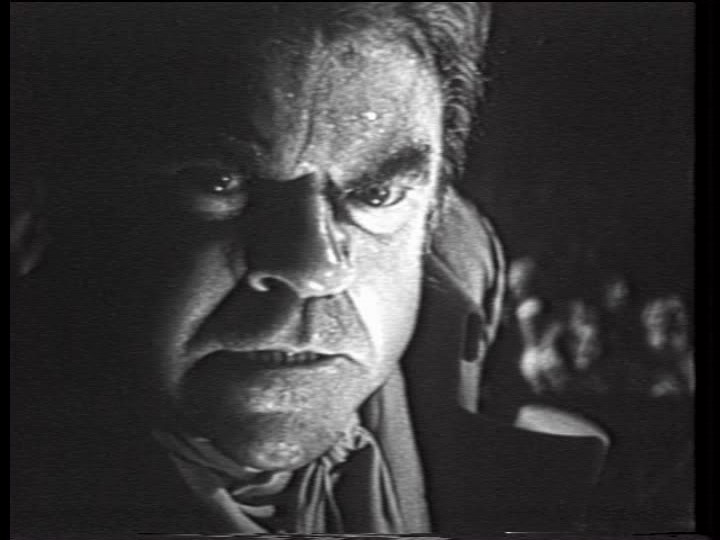

Embarrassingly, this is my first Cronenberg film. Also somewhat embarrassingly, I'm still unsure of my initial reaction to it -- as I was watching it, I think I was dismissing a lot of it as trite, rolling my eyes at some of the '80s-movies bullying of Viggo Morensen's son, for example. I mean, the kid catches a fly ball in gym class and it sets off the class douchebag? Isn't he supposed to hit on his girlfriend or something?

Embarrassingly, this is my first Cronenberg film. Also somewhat embarrassingly, I'm still unsure of my initial reaction to it -- as I was watching it, I think I was dismissing a lot of it as trite, rolling my eyes at some of the '80s-movies bullying of Viggo Morensen's son, for example. I mean, the kid catches a fly ball in gym class and it sets off the class douchebag? Isn't he supposed to hit on his girlfriend or something?But what I think I missed is that Cronenberg was using these cliches and exaggerating them in some cases in order to explore his and his audience's reactions to violence. Another example of this is the town of Millbrook, Indiana, in which Mortensen's family lives. Here's Cronenberg on the setting in a Village Voice interview:

It's perversely idealized. It's almost Twilight Zone-y. There's an appeal to that longing for an imaginary past -- a yearning for an innocence that was never so pure anyway. It's meant to be recognizably real, but it has to play as mythological as well. That's part of the balancing act.

On the other hand, the same poster, who admits he loves the film, says "the inherent problem of the film is that it chooses to undermine the conventional revenge flick by emulating it to excess." That excess is what I saw the first time around more than the undermining, but in reading and writing about the film, I'm starting to understand the subversion much better.